Stress is a natural part of the human experience, but how we can regulate how we cope with its presence? Chronic stress and trauma create rigidity and tension within body tissues that leave our responses less adaptable and link them to inflammatory and structural issues. Add in that much of modern stress is within sedentary behaviour patterns that don’t allow us to physically express when we are angry, sad or in pain. Recent interest in movement as ‘body psychotherapy’ describes how we process much of our unconscious thought via our physical body.

A 2014 review of mindful movement research called Movement-based embodied contemplative practices: definitions and paradigms (Front Hum Neurosci. 2014; 8: 205) discussed how, over the past decades, cognitive neuroscience has witnessed a shift from predominantly disembodied and computational views of the mind, to more embodied and situated views of the mind. Put simply, to separate out mind from body is to miss intricate links between our mental processes and our gestures and motions.

The paper discussed the literature on how practices such as yoga, Qigong, and T’ai Chi, that are grounded in the concepts of embodiment, breath awareness, movement and contemplation cultivate kinaesthetic awareness. Kinaesthesia is often referred to as our ‘sixth sense’ and brings together interoception (sensing our internal landscape) and proprioception (sensing our position in space and sense of self). Modern somatic therapeutic techniques such as the Feldenkrais Method and the Alexander Technique also foster this embodied awareness that allows us to feel the safety of knowing where we are and how we feel, beneath the heightened reactions of stress.

The review states; “Embodied activity, including cognitive processes, takes the form of sensorimotor coupling with the environment. What a living organism senses and perceives is a function of how it moves, and how a living organism moves is a function of what it senses and perceives.” This helps us to understand and prioritise mindful movement for our coping capacity in the face of stress.

Adrenal Response Exercise

This exercise is aimed at resetting the adrenal response to mimic the transition usually made from when we move from the startle response seen in babies to the more developed ‘fight-or-flight’ response seen in adults. Babies’ limbs all open suddenly outwards in response to stress, but beyond about a year, we change to curl inwards for self-protection. At this point reactions to every change in light, movement, touch, sound, temperature, hunger, thirst are inhibited; babies need a highly sensitive level of response as they cannot distinguish what it safe or unsafe and need to alert a caregiver to help and protect them.

As we become more able to help ourselves, we also become discerning about what we see as danger, rather than reacting to any stimulus as if it were a threat. Those with early trauma, lack of attachment or attunement when young (or maybe illness, it is theorised) may not fully develop these ‘filters’ and continue to respond to any change (even very subtle) as if it were a true danger. Those suffering trauma or chronic stress later in life may also come back to this heightened sensitivity and feel the world a harsh place to navigate. Noise and light sensitivity are key signs of stress overload, where a person stays locked in protective sympathetic fight-or-flight mode and retains a continual vigilance of heightened senses.

Meditation has shown to lessen this retained primitive startle response in adults (Emotion. 2012; 12(3): 650–658) and meditative movement such as the exercise below helps to reset the head, neck and shoulder responses to nervous system input. It also creates a conscious imprint of the different tones of the breath. Those with chronic stress can often be disconnected with when they are breathing in, and out.

If possible, do regularly around the same time every day, for instance when you wake up or get in from work. These are times we transition from one mode of being to another and may struggle to adapt without a protective response; become more stressed as we start the day, or numbing with sugar or alcohol when stress hormones come down.

It can also be done any time, including as a soothing, rocking, meditative motion when you feel most overwhelmed or overtaken by cravings. Our body feels safe when we synchronise breath and movement.

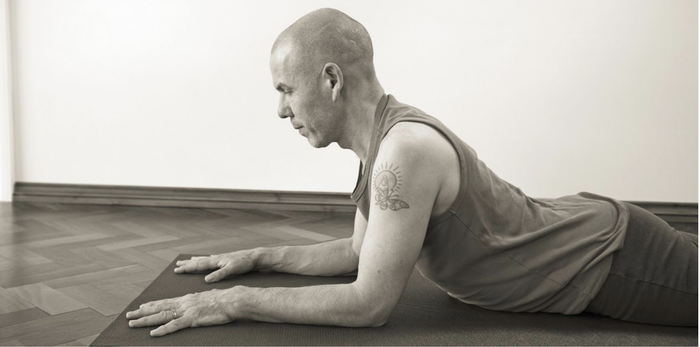

- Lie on your back, spread-eagled with your arms and legs spread wide. This is the inhale position, where we open the ventral or front body – this opens us up to meet the world with our soft, vulnerable throat, heart and belly and is a gesture of action and courage, but also receptivity, ready to meet the world. This energising, in-breath position is paired with the sympathetic nervous system and hence such positions (usually upright) are often referred to as “power poses”; here is where we occupy our space and potential.

- Breathe out fully as you roll to one side, drawing all limbs in to a full foetal position with arms and legs pulled into the body, hands and feet soft. On the exhalation we open the dorsal or back body to curl us in (via psoas flexion) and is a gesture of protection paired with the calming, parasympathetic out-breath. A foetal position fully draws us in to protect our soft front body, rounding the lower back and neck as when we were babies, before we moved upright and our secondary, inward curves develop there.

- Move between these two positions, alternating the exhale position side-to-side, with movement lead by the breath, finding the smoothest transitions between the two possible. It may feel jerky or mechanical to start, but letting the breath lead will allow you to find free-flow.

- You can repeat around 20 times each side, continually moving, or move to change position with the breath whenever feels right, even resting in either if you need to catch up with the breath.

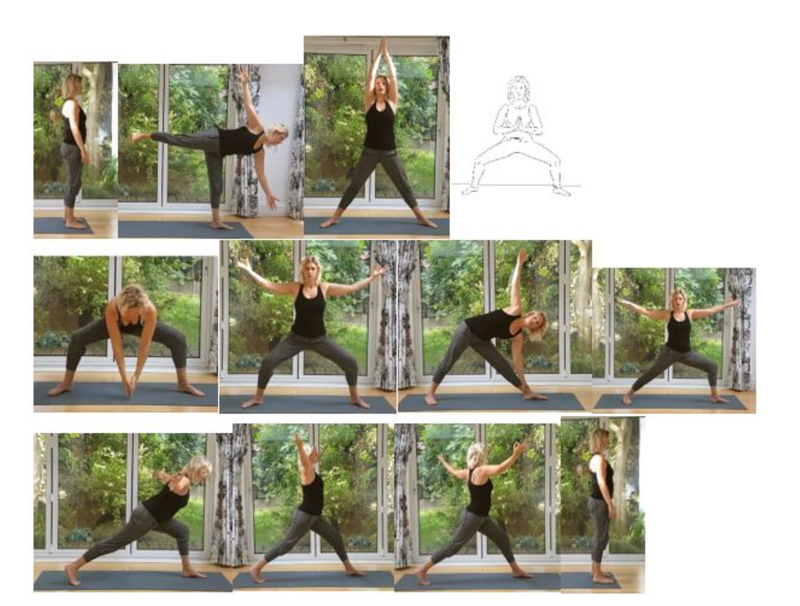

Standing sequence from feet

This sequence fosters the kinaesthetic quality of feeling ‘grounded’. That means to have a full sense of our physical body, where it is, the shape and volume it is, right now in time and space. When freeze and dissociation (feeling spacey and ‘not here’) from stress or trauma tend to take us away from this clear experience of the present moment, embodiment – particularly feeling feet and legs - provides a tether to come back to. Grounding can come from lying or from standing up from the feet; for those with deep trauma at times it may be most appropriate to start standing for a strong sense of the self.

As Bessel van der Kolk says in his seminal book on trauma, The Body Keeps the Score; “You can be fully in charge of your life only if you acknowledge the reality of your body in all its visceral dimensions.”

- Begin in tadasana (mountain pose), standing feet hip-width apart, feet parallel and taking time to settle your breath into your feet.

- Keeping the left foot parallel to the outside of the mat, from bent legs open into ardha chandrasana (half-moon pose), drawing the legs to straight and hanging the bottom arm off the ground. Your focus can be downwards here to be able to steady enough to revolve belly and chest upwards. Balance focuses our proprioception keenly and teaches us to steady the mind, the gaze and breathe fully to stay, rather than ‘hold it all together’ with tension.

- Bend the standing leg to boldly step the top leg into horse stance, shifting on the feet as you move to bring them 90 degrees apart. Draw up through the belly to support the lower back and lengthen the inner thighs to keep the knees pointing in the direction of the toes.

- Inhale the arms out to the sides and up together above the head, as you draw legs up to straight.

- Exhale down the centre line, through hands to heart and then inhale all the way out and up to the starting position in fig.4.

- Continuing this movement, you may even reach down lower to touch fingertips to the ground, if your hips allow and it stays comfortable for your knees. Find your range of motion for any given day, modulating for how you feel in the present, not how far down you want to go. From here we can cultivate a kind and accepting, rather than and punitive and pushing relationship with our body.

- Hold an open horse stance, arms out to the side, hands held above the shoulders. Here you can soften down the inner edge of the shoulder blades and feel the arms held up from the belly, not shoulder tension. Breath here to feel the sensations of building strength, feeling full exhalations allow us to be with stronger sensations as we feel intensity; this helps build resilience.

- Move the feet to lead you into trikonasana (triangle pose) with the front foot (left to start) parallel to the outside of the mat and the back foot turned in 90 degrees to also revolve that hip in. Draw up through both legs to feel the support to revolve the belly and chest to the ceiling, only bringing the bottom hand down to where you can still find that action. Strong legs and active feet, with full breath then allow us to tune into the movements of the spine to foster interoception.

- Circle the top arm back and round to come up into virabhradrasana 2 (warrior 2 pose), reaching out both arms equally from the centre and as with trikonasana, turning the back hip in to allow length in the inner front thigh where you can keep the front knee pointing towards the toes, without strain on the lower back. As with horse stance, hold the hands above the shoulders, breathing in towards intense sensations, exhaling to stay with soft jaw, eyes and attitude.

- Lift the right heel (back leg) to be able to turn the hips to face the direction you started in tadasana, moving the front foot out from the midline enough to feel you have the feet hip-width apart and parallel to the outsides of the mat. Open the arms as you did in horse stance feeling open across the collarbones for full breath. Only come down to bend the front knee as far as your right-side (back leg) front body lengthens without pulling on the lower back, so where you can still draw up the belly from just above the pubic bone. This is working intelligently, where we foster resilience, without telling the nervous system this is a stressful event.

- From there, turn the belly into a twist, retaining space at the tops of the thighs to not collapse in there. Twists encourage circulation around the adrenals and into the fascia between and around all organs, to keep the hydration that eases movement and adaptability – physically and mentally.

- Come back to centre, open the arms out to the side, palms down to reach out from the collarbones and drop the torso, belly to thigh. In this ‘humble warrior’ pose, lengthen the whole body, back heel to crown of the head as if the whole left side was in tadasana, looking forward and down, so back and sides of the neck stay long. This is a position of both strength and surrender, polarities we need to be able to move with life’s changes with flexibility and ease.

- Bounce into the feet, bending the back leg to create some elastic loading up through the fascia to step the back leg back up to tadasana. Step the back foot in halfway if you need, rather than struggle to step up, noticing how we can adapt to not force or strain our way into postures. Ultimately this builds strength without injury and frees our mind from stressful attachment to how our body “should be”. Breathe here, earthing back down into the feet before moving to the other side.

Meditation Teacher Certification

1st October 2025 • Online Live • Graham Burns Isabell Britsch

- Details and booking

Yoga & Somatics for Healing & Recovery Online Training

25th September 2025 • Online Live • Charlotte Watts

- Details and booking

Menopause Yoga Teacher Training (suitable timings for North America)

2nd June 2025 • Online Live • Petra Coveney

- Details and booking

Menopause Yoga Teacher Training

2nd April 2025 • Online Live • Petra Coveney

- Details and booking

Birthlight Postnatal Yoga Teacher Training

17th October 2025 • Online Live • Kirsteen Ruffell

- Details and booking

Yin Yoga Teacher Training: Minds, Meridians, Moments (In Person)

24th November 2025 • West London Buddhist Centre • Face to face • Norman Blair

- Details and booking

Teen Yoga Teacher Training (Online)

16th September 2025 • Online Live • Charlotta Martinus

- Details and booking

Teen Yoga Teacher Training (In Person)

7th April 2025 • Old Diorama Arts Centre • Face to face • Charlotta Martinus

- Details and booking

The Art of Sacred Sound Training

12th April 2025 • Online Live • Anne Malone

- Details and booking